Get Your All-Flo Pumps and Parts Now With FREE SHIPPING - Ends 2/28. SHOP NOW >

Pumps for Industrial Chemical Transfer Systems

Industrial chemical transfer systems fail when pump materials, sealing strategy and operating assumptions do not align with the chemical environment. Reliable chemical transfer depends on selecting pumps that tolerate chemical attack, variable viscosity and real suction conditions while maintaining containment over long operating intervals.

Contributors

This page was developed using expert insights from PSG® subject matter experts with extensive experience in chemical processing, hazardous fluid handling and industrial pumping systems.

Chemical transfer is not simply moving liquid from one vessel to another. It is a materials science problem operating inside a mechanical system. Unlike water or fuel service market applications, many industrial chemicals actively attack pump components over time, often without immediate or obvious failure.

Chemical transfer systems routinely handle corrosive fluids, aggressive solvents, acids, caustics and specialty additives. These fluids may be thin or highly viscous, temperature sensitive or reactive with common elastomers and metals.

Failure rarely occurs instantly. Instead, pumps degrade quietly until leaks, loss of performance or contamination force unplanned shutdowns.

The engineering objective in chemical transfer is therefore long-term containment and predictable wear behavior, not just initial flow delivery.

Defining Chemical Transfer Duty Beyond Flow and Pressure

Specifying chemical transfer pumps based only on flow rate and pressure is one of the most common sources of misapplication. Chemical service must be defined by how the pump behaves as materials degrade over time.

Key inputs include chemical identity, concentration and operating temperature. Exposure time matters as much as chemistry itself, as short-term compatibility does not guarantee long-term survivability.

Viscosity changes with temperature alter internal clearances, torque requirements and slip. Solids formation, crystallization or polymerization increases abrasion and valve wear.

Equally important are system realities such as suction quality, air ingestion, intermittent operation and flushing practices. Many chemical pumps fail not because the pump was undersized, but because the system assumed ideal suction conditions or perfect operating discipline.

Chemical Compatibility: Why Failures Are Slow, Cumulative and Expensive

Chemical incompatibility rarely causes immediate pump destruction. Elastomers may swell, shrink or soften over weeks or months. Plastics may craze or embrittle. Metals may pit or corrode beneath coatings. These effects manifest as leaks, sticking valves, diaphragm rupture or seal failure long after installation.

Field experience shows that many repeat failures trace back to elastomer selection rather than pump design. Compatibility charts must be interpreted conservatively and adjusted for temperature, concentration and continuous exposure rather than short-term testing.

The safest approach is to assume the chemical will be present for longer, hotter and more aggressive conditions than planned, and to select materials accordingly.

Sealing Strategy and Containment Risk

In chemical transfer, containment is often more critical than efficiency. The cost of a leak may include environmental exposure, personnel risk, cleanup cost and regulatory reporting.

Traditional sealed rotating pumps introduce a dynamic seal as the primary failure point. Mechanical seals will fail over time, particularly in chemically aggressive or abrasive service.

Seal-less designs, such as magnetically driven gear pumps from manufacturers like Blackmer®, eliminate this failure mode entirely by removing the shaft penetration.

Seal-less pumps are therefore commonly selected for hazardous, toxic or high-value chemicals where leakage cannot be tolerated. While seal-less designs may carry a higher upfront cost, they significantly reduce long-term risk and maintenance burden.

AODD Pumps in Chemical Transfer: Why Flexibility Often Outweighs Efficiency

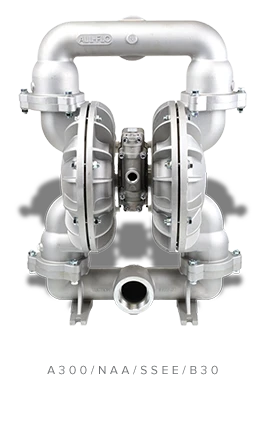

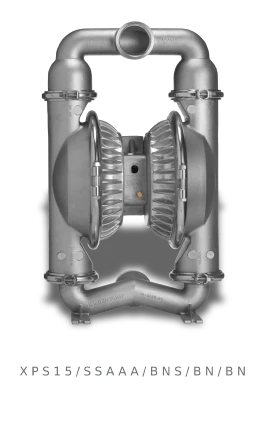

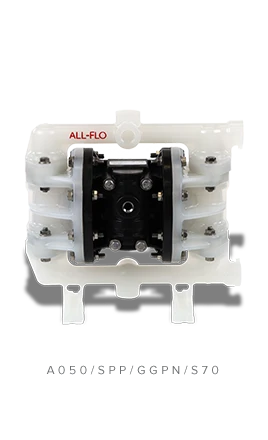

Air-Operated Double Diaphragm (AODD) pump technology are widely used in industrial chemical transfer because they tolerate conditions that damage or disable other pump types.

AODD pumps handle variable viscosity, air ingestion and intermittent duty without losing prime. They stall safely when discharge is blocked and contain no dynamic shaft seals. These characteristics make them well-suited for unloading, batch transfer and chemical distribution systems.

Products from manufacturers such as Wilden® and All-Flo™ are commonly selected for chemical service because diaphragm and valve materials can be tailored to specific chemistries.

While AODD pumps produce pulsating flow and rely on defined wear components, failures are typically contained within the wet end rather than resulting in uncontrolled leaks when proper materials are selected.

Gear and Centrifugal Pumps: Where They Fit in Chemical Service

Gear pumps excel in chemical applications involving higher viscosity fluids, precise metering and steady operating conditions. Tight internal clearances deliver consistent flow but demand clean fluids and careful material selection.

Seal-less gear pumps are often preferred for hazardous chemicals where containment is critical.

Centrifugal pumps are typically limited to lower-risk chemical services such as flushing, cleaning or transferring non-aggressive fluids. Designs from manufacturers such as Griswold® perform well when suction conditions are stable and viscosity remains low.

However, centrifugal pumps are sensitive to vapor, air ingestion and viscosity changes and therefore require conservative system design when applied in chemical environments.

Selecting these technologies successfully requires a realistic assessment of how stable the process truly is over time.

Temperature, Viscosity and Exposure Time

Temperature magnifies chemical attacks. A material compatible at ambient conditions may fail rapidly at elevated temperatures. Viscosity changes alter pump loading, efficiency and slip and may shift a pump outside its optimal operating range.

Exposure time is often overlooked. Pumps that are continuously exposed to chemicals behave very differently from those that are flushed and isolated between batches. Selection must reflect actual duty cycles, not idealized process descriptions.

Designing for Maintenance and Predictable Wear

Industrial chemical systems are often maintained by small teams responsible for many assets. Pumps must be serviceable with available skills and tools.

AODD pumps allow wet-end rebuilds without disturbing piping. Gear pumps require more controlled maintenance but offer long life when conditions are stable. Centrifugal pumps require disciplined seal management and monitoring.

Standardizing pump platforms, materials and genuine spare parts can reduce error and improve response time during failures.

For initial technology narrowing, tools such as the pump finder can help align fluid properties with pump families.

Chemical transfer failures often result from system interactions rather than pump defects. Suction layout, venting, flushing strategy and material transitions all influence outcomes.

Engaging application specialists early reduces misapplication risk and improves long-term reliability. Support is available through the contact us page.

For additional information, please review our returns policy, shipping policy and terms and conditions, including our terms of use.

Contributors

Rob Jack

Rob Jack is a technical authority on AODD pumps with decades of experience diagnosing chemical compatibility issues, diaphragm failures and system-level misapplications in industrial environments.

Jeff Peterson

Jeff Peterson has extensive experience with gear and seal-less pump technologies for chemical transfer. His background includes hazardous chemical handling, viscosity-driven pump selection and containment-focused system design.

Steve Cox

Steve Cox brings broad industrial experience across diaphragm, vane and centrifugal pumps with a focus on serviceability, reliability and long-term lifecycle cost in chemical and industrial markets.

Frequently Asked Questions About Industrial Chemical Pumping

Industrial chemical transfer involves fluids that actively attack pump materials over time through corrosion, swelling and chemical degradation. Unlike water or fuel service, long-term reliability depends on material compatibility, containment strategy and predictable wear rather than just flow rate and pressure.

Chemical incompatibility causes gradual failure of elastomers, plastics and metals, leading to leaks, loss of performance and unplanned downtime. Compatibility must account for temperature, concentration and continuous exposure, not just short-term testing conditions.

Chemical transfer systems often use air-operated double diaphragm pumps for hazardous or high-value fluids and centrifugal pumps where fluids are clean, stable and less aggressive.

Sealing is often the primary failure point of chemical service. Mechanical seals wear and degrade over time under chemical attack, while seal-less designs eliminate dynamic sealing surfaces and reduce leak risk in aggressive or regulated environments.

Higher temperatures accelerate chemical reactions and material degradation, while continuous exposure compounds wear and swelling. Materials that perform acceptably in intermittent service may fail quickly in continuous chemical transfer applications.

Chemical pumps should be selected based on worst-case fluid chemistry, temperature range, expose duration and system behavior rather than nominal operating conditions. Designing for containment, predictable wear and maintenance reality improves uptime and lowers lifecycle cost.

Find Your Pump

Just answer a few questions, and our Pump

Finder will guide you to the right solution!

PUMP FINDER